Public health professionals grapple with the world’s biggest health problems, tackling challenges such as poor nutrition, avoidable chronic diseases, maternal mortality, and antibiotic resistance. But how can public health professionals understand the problems they confront? Where do they find their methods? How do they know which strategies to deploy?

Public health research plays an essential role in understanding the factors that lead to poor health and identifying ways to address them. Public health researchers get to the bottom of health issues, finding answers to questions such as:

- Why is this group not getting recommended cancer screenings?

- What is preventing a community from receiving prenatal care?

- Why has a population consistently failed to complete the full course of prescribed antibiotics?

Understanding the reasons behind health issues allows public health researchers to focus on another important fact-finding mission: identifying effective interventions. Research also seeks to answer questions such as:

- Is this intervention model viable, and can it be reproduced effectively?

- How should this intervention be implemented?

- Can this model be adapted to work in a variety of conditions?

While many public health professionals are driven to implement interventions, others are inspired to engage in the life-saving research at the root of those interventions. Tulane University offers an Online Master of Public Health program designed to build foundational skills in public health research and examine how research applies in real-world practice.

Careers in Public Health Research

Opportunities in public health research abound. Whether protecting a community from vehicular death or examining techniques that increase vaccination rates, public health researchers dig into subjects ranging from bioterrorism to mental health. Public health research professionals analyze health trends and environmental risks in communities and use the information they uncover to innovate solutions and educate the public.

Public health researchers take on different educational, analytical, technical, and administrative roles in their work. For example, they may:

- interview community members to collect data, then use that data to create statistical models

- conduct various types of studies, and analyze their findings to propose public health policies

- study large databases that contain health information to gain insights about health issues, and then develop health promotion programs

- develop presentations or initiatives to educate the public about health issues

Where Do Public Health Researchers Work?

Many types of institutions employ public health researchers. Most university faculty members in schools of public health, for instance, are public health researchers in addition to being educators. As part of a university, they benefit from the institution’s resources and partnerships that can help facilitate their research.

Non-governmental organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) also hire public health researchers. Within these organizations, public health researchers study everything from how to crack down on plastic pollution to how climate change has increased incidences of sleeping sickness in Tanzania.

The government, both at the federal and state levels, rely on public health researchers’ work to address disaster preparedness, preventable chronic illnesses, maternal health, and other public health concerns.

Agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conduct extensive public health research, and collaborate with the Prevention Resource Centers (PRCs), a network of 26 academic research centers across the U.S. Public health researchers in this network engage in research projects with community partners to develop solutions to address high disease rates in underserved communities.

What Do Public Health Researchers Do?

By drawing on epidemiology, biostatistics, and social sciences, and applying them to health and biology, public health researchers formulate reports and interventions that protect populations, educate communities, and help influence healthcare policies. Their interdisciplinary work uses specific tools, including:

- Survey campaigns: questionnaires or interviews given to targeted community members for the purpose of collecting data for statistical analysis to better understand beliefs, behaviors, health conditions, or other characteristics

- Community data analysis: the analysis of large amounts of data about a community that is then broken down into insights about their health, behaviors, or other characteristics

- Cohort studies: studying groups with similar characteristics over time to identify a disease or health condition as well as identify risk factors

- Case control studies: studying groups with and without a specific health condition and examining data from both groups to identify protective and risk factors

- Morbidity registries: databases that contain large amounts of information about a population’s health conditions in a specific location

What is the Job Outlook for Public Health Researchers?

People entering the public health research field can expect rewarding work. The job outlook for these positions is promising. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the number of public health research positions is projected to grow 8 percent by 2028. The median public health researcher salary was $88,790 in May 2019. These numbers vary by industry.

How to Become a Public Health Researcher

Aspiring public health researchers must thoughtfully plan how to acquire the training, experience, and skills needed to pursue their career goals. While different paths can lead public health researchers to success, the following steps serve as a useful guide.

Step One: Earn a Bachelor’s Degree

Public health researchers can choose to study public health for their bachelor’s degree or other areas useful to public health research such as the social sciences. Some public health researchers earn their bachelor’s degrees in the hard sciences. Others choose to focus on a subject of particular interest to them, such as women and gender studies.

Step Two: Earn a Master’s Degree

After earning a bachelor’s degree, public health researchers can pursue a Master of Public Health (MPH). This degree builds a foundation in public health’s core areas:

- Epidemiology: What can cause diseases, and how can diseases turn into public health crises?

- Behavioral science: What can motivate people to make healthy decisions?

- Biostatistics: How can data be used to assess and tackle health risks?

MPH programs also cultivate management skills, key to collaborating and communicating with communities and influencing policymakers regarding public health. Additionally, MPH programs allow students to apply their knowledge in practicums as well as residencies across the country and abroad.

Based on their interests, students can choose where they complete their practicums and residencies. For example, some Tulane University MPH students have traveled to Peru to finish their research practicums alongside faculty. These types of hands-on experiences can serve as stepping stones for aspiring public health researchers to develop their own initiatives and projects around the world.

Step Three: Gain Work Experience

MPH programs give public health researchers the foundation needed to begin work in many areas of public health including:

- Health education

- Program development and management

- Healthcare environment

- Foreign aid

Working in a specific area of public health or public service for several years can provide the skills and experience in public health research methods that are needed to conduct the most valuable and effective public health research.

Examples of Public Health Research

Public health research covers a broad range of topics. At Tulane, for example, faculty are conducting research on everything from lead poisoning in children to the impact of race disparities on health.

Cervical Cancer Prevention in Peru

Dr. Valerie A. Paz-Soldan, associate professor and director of Tulane Health Offices for Latin America, developed an interest in public health while growing up in Peru. She wanted to find solutions to health problems that could affect large numbers of people, especially marginalized people without the money to access needed resources.

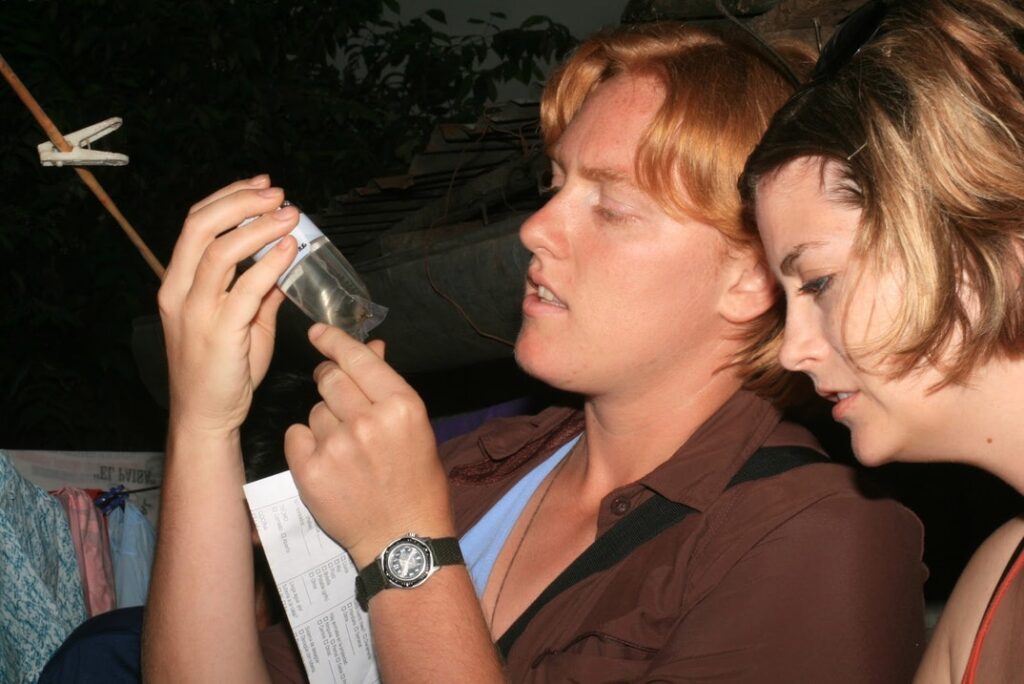

Based in Iquitos, Peru, a city of around 400,000 in a rainforest only accessible by plane or boat, Paz-Soldan focuses her research on several public health issues. One concerns cervical cancer screening. The region where she works has low cervical cancer screening rates and the country’s highest incidence of cervical cancer. Paz-Soldan’s research has sought to understand why that is and how to remedy it.

Through careful study, Paz-Soldan discovered many women in the region failed to get screenings because they ran into significant barriers when they tried. To reach healthcare facilities, many had to make journeys several hours long. Sometimes they arrived for screenings and found no one to administer tests.

Additionally, Paz-Soldan’s research found that the relatively invasive nature of a method for early cervical cancer detection, the Pap smear, discouraged many women from getting screened. For example, indigenous women often did not get Pap smears due to cultural views that made them uncomfortable with pelvic exams.

Of the women who did have Pap smears, 50 to 70 percent did not get the prescribed tests and treatments when abnormal cells were found on the cervix. When Paz-Soldan interviewed these women to find out why, she learned that many made three to four attempts to follow up but encountered obstacles, such as absent doctors or blood tests they had no money to pay for.

By examining how the Pap smear screening system kept losing women along the way, Paz-Soldan realized that the system, meant as an intervention to cervical cancer, was only reaching 2 percent of the women it was intended for. With this understanding, Paz-Soldan sought to change the screening system to one based on HPV testing, a test that detects the sexually transmitted disease human papillomavirus, which can lead to cancer.

Paz-Soldan found that though more expensive, HPV tests offered significant advantages over Pap smears because of their quicker results and the fact that they allow women to swab themselves. She explains that HPV tests are an evidence based tool that allows them to, “look for the virus, way before it actually causes cancer cells or abnormal cells or causes lesions.”

By switching to a cancer screening system based on HPV testing, Paz-Soldan and her colleagues have significantly increased the number of women getting screened. She projects that at the current pace, 91 percent of women in the region will get cervical cancer screenings by the end of 2020.

Women’s Health in Ethiopia

Another Tulane faculty member, Dr. Anastasia J. Gage, researches topics that include adolescent health and maternal and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa.

One of her past projects examined child marriage in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, where girls were married before they reached age 15 on average. Specifically, Gage’s research sought to assess the effectiveness of different intervention methods intended to delay these marriages and shift local attitudes about child marriage.

While child marriage might not seem like an obvious public health issue, in fact, it can cause emotional harm and pose physical health risks to the girls. For example, Gage found high rates of obstetric fistulas in the Amhara region.

When physically immature girls try to give birth, often their pelvises are too small for the baby’s head to pass through. As a result, the delivery can cause death to the mother and child or create internal tears that leave the mother leaking urine and feces. Communities then ostracize these young mothers.

Gage’s research examined a community-developed intervention called community conversations to assess whether it could influence the attitudes of those arranging child marriages. Community conversations involved discussions about reasons to delay marriage until a girl is over age 18. Community members conducted them in the family homes of girls with impending marriage arrangements.

Though child marriage remains an issue in the Amhara region, Gage found that community conversations have made a difference and that the age of girls getting married in Amhara is slowly rising. It was illuminating, “to see how change can be brought about if girls, their community members, school teachers, policemen, religious leaders, work together to bring about attitudinal change.”

The Importance of Community Collaboration

Public health professionals strive to promote healthier communities and prevent disease using science-based solutions. Through research, public health professionals can find the best ways to address the conditions of where people live, work, and play that make them sick—but meaningful community collaboration is vital to the success of public health research initiatives.

Dr. Gage explains, “At the very beginning, before you plan an intervention you might want to do formative research to understand the people who would be affected by your intervention.” This promotes community understanding: Individuals inevitably understand their own obstacles better than anyone else.

By surveying communities or conducting focus groups, public health professionals discover workable solutions. They also gain critical insights into how to design or modify effective interventions.

Often the ideas and visions of community members, uncovered during formative research, play critical roles in forming public health solutions. Without these insights, public health professionals shoot in the dark.

Additionally, the research sheds light on which aspects of an intervention are working. Ultimately, research improves the chances of a project achieving its goals.

To be effective, public health professionals need to collaborate with the communities they serve, including incorporating the community members’ ideas into their proposed solutions. Uncovering those ideas and ensuring a public health program succeeds is indeed a collaboration, requiring research.

Collaboration in Action

One of Dr. Paz-Soldan’s public health projects aimed at controlling dengue fever transmission demonstrates the importance of community collaboration.

Dengue fever, a mosquito-borne disease, can cause painful and serious symptoms. While collaborating with community members to design interventions, she discovered that insecticide-treated curtains meant to stop mosquitoes from entering people’s homes and spreading the virus were not practical. They blocked wind from cooling the homes, so people didn’t want to use them.

Similarly, she discovered that proposed insect traps needed to meet certain design requirements. For example, the designs had to account for the frequent flooding in people’s homes and address people’s concerns about animals or children getting into them. “Using this qualitative research along the process allowed us to make modifications to the study,” explains Paz-Soldan.

Without continuous community input and research, Paz-Soldan’s interventions may not have been as effective—and the same is true of countless other public health initiatives around the world. Paz-Soldan points out that knowing your audience is fundamental to effective public health efforts, and research builds that knowledge.

Explore the Master of Public Health Degree Program

Without public health research, health professionals can do little more than guesswork when trying to understand why a region has an exceptionally high cervical cancer rate, or determining if a specific intervention can indeed influence families to wait until their daughters turn 18 before they allow them to marry.

With the right education, public health researchers can uncover critical information about the unique circumstances and conditions of the particular communities they serve. In addition, by cultivating their research expertise, public health researchers can develop more effective intervention methods.

Tulane University offers an advanced degree program in public health designed to deepen knowledge about health equity, monitor and evaluate public health programs, apply health communication theory, and use social innovation tools. With this training, graduates can successfully conduct the critical research needed to tackle the most challenging health problems.

Inspired by the opportunity to serve marginalized people and ensure health equity across all communities? Discover how an Online Master of Public Health from Tulane University prepares graduates to research innovative solutions that can change lives.

Recommended Readings

Healthcare Analytics: A New Frontier for Public Health

What Is Health Equity? Ensuring Access for Everyone

Sources:

American Public Health Association, “Public Health Code of Ethics”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention Research Centers

Houston Chronicle, “Job Description for Researcher in the Field of Public Health”

Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology, “Understanding and Evaluating Survey Research”

Public Health Ethics, “Public Health Research”

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Medical Scientists